Years ago, on a harsh winter morning in Ladakh in

the northernmost Himalayas in India, a young and curious boy in a

remote mountain village of the cold desert, watched as water came

out of a semi-frozen pipe, collected in a small crater on the

ground and froze instantly, just like a glacier.

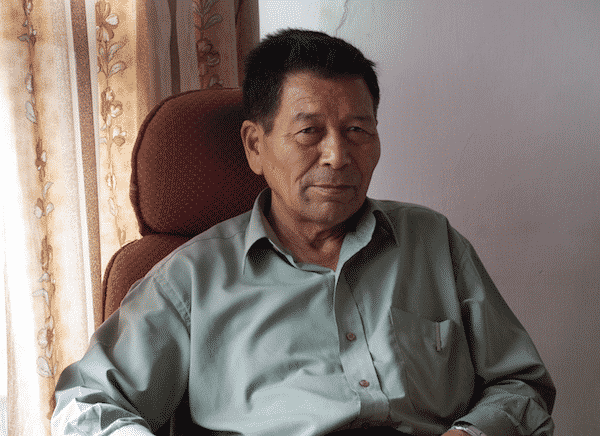

Decades later, the boy, Chewang Norphel – now a civil

engineer with the Jammu and Kashmir Rural Development Department –

took inspiration from his childhood observations and devised an

‘artificial glacier’ to solve the water crisis in his

community.

Spurred by the success of his experiment, he went on to

create 17 such artificial glaciers across Ladakh, thereby earning

his nickname, “The Ice Man of India”.

Most of his projects received financial aid from

several state-run programs, the army and various national and

international NGOs.

Now an 80-year-old source of inspiration, Norphel’s

journey was not easy, as people initially used to laugh at him and

called him “pagal” (crazy).

But that did not deter him, as all he saw was a grave

water problem which needed a solution – and he had

one.

The rivers in the region are the main source of fresh

water, but since they flow at lower altitudes, they are of no use

to villages at relatively higher altitudes.

The farmers in the region only have access to flowing

water in June, when the natural glaciers, situated some 5,000 feet

above and 20-25 km away from the villages, melt annually.

“At the time of sowing in April-May, the glacial

streams are frozen and rivers flow way too low to fetch water,”

Norphel described.

The water that flowed through the lower regions in the

winter months, was often wasted.

The solution was, to find a way to store this wasted

water. “So I thought: what if there were glaciers at lower

altitudes which would melt sooner due to relatively higher

temperature? Thus came the idea of artificial glaciers. It’s a

technique to harvest winter waste water in the form of ice. And by

creating artificial glaciers at relatively lower altitudes, it was

possible to get water when it was needed,” Norphel said.

The work to construct a glacier starts in October when

the villagers divert the glacial streams, and create embankments in

the form of steps to slow down the velocity of water.

“We assure that the depth is kept only a few inches, so

that it freezes easily,” he said.

Norphel has built glaciers at the toughest terrains in

Ladakh including one at Dha, the native village of the Brokpa tribe

which is renowned in the entire region for their distinct culture

and their role during the Kargil war.

But close to his heart is the 1,000-feet-wide glacier

that he built at the Phukte valley which supplies water to five

villages. The glacier was built at the cost of approximately Rs

90,000.

Norphel said that the cost of an artificial glacier

today could go up to Rs 15 lakh, depending on its size and

capacity.

“No one took me seriously (in the beginning); today

they all are benefited,” says the humble old man, rarely seen

without a pleasant smile on his face. “These glaciers are my pride

and the fact that my concept has helped so many people gives me

peace of mind.”